Ettore Bugatti, coming from a family of successful artist, brought automotive craftmanship to a higher level with the design and manufacture of cars baring his name. Many describe these cars as rolling art and the pinnacle of pre-WWII automobiles. They were inspirational for contemporaries and the generations that followed. Bugatti was one of Enzo Ferrari’s greatest heroes.

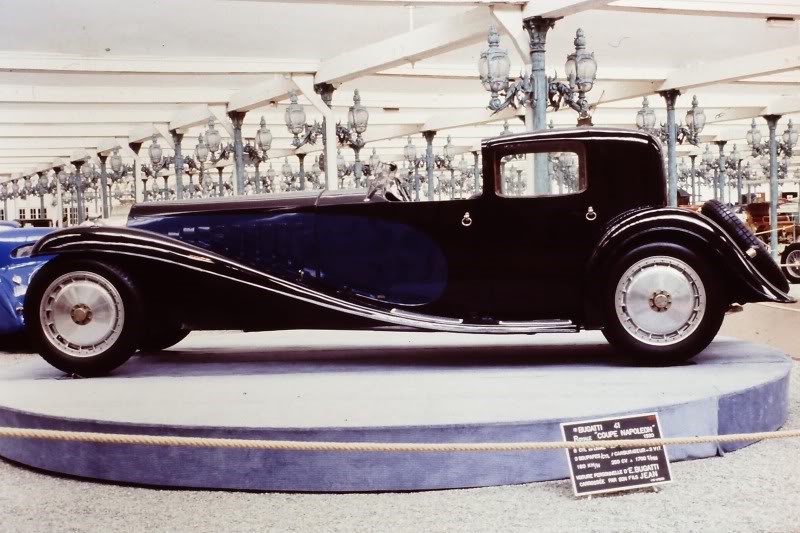

Type 41 Royale’

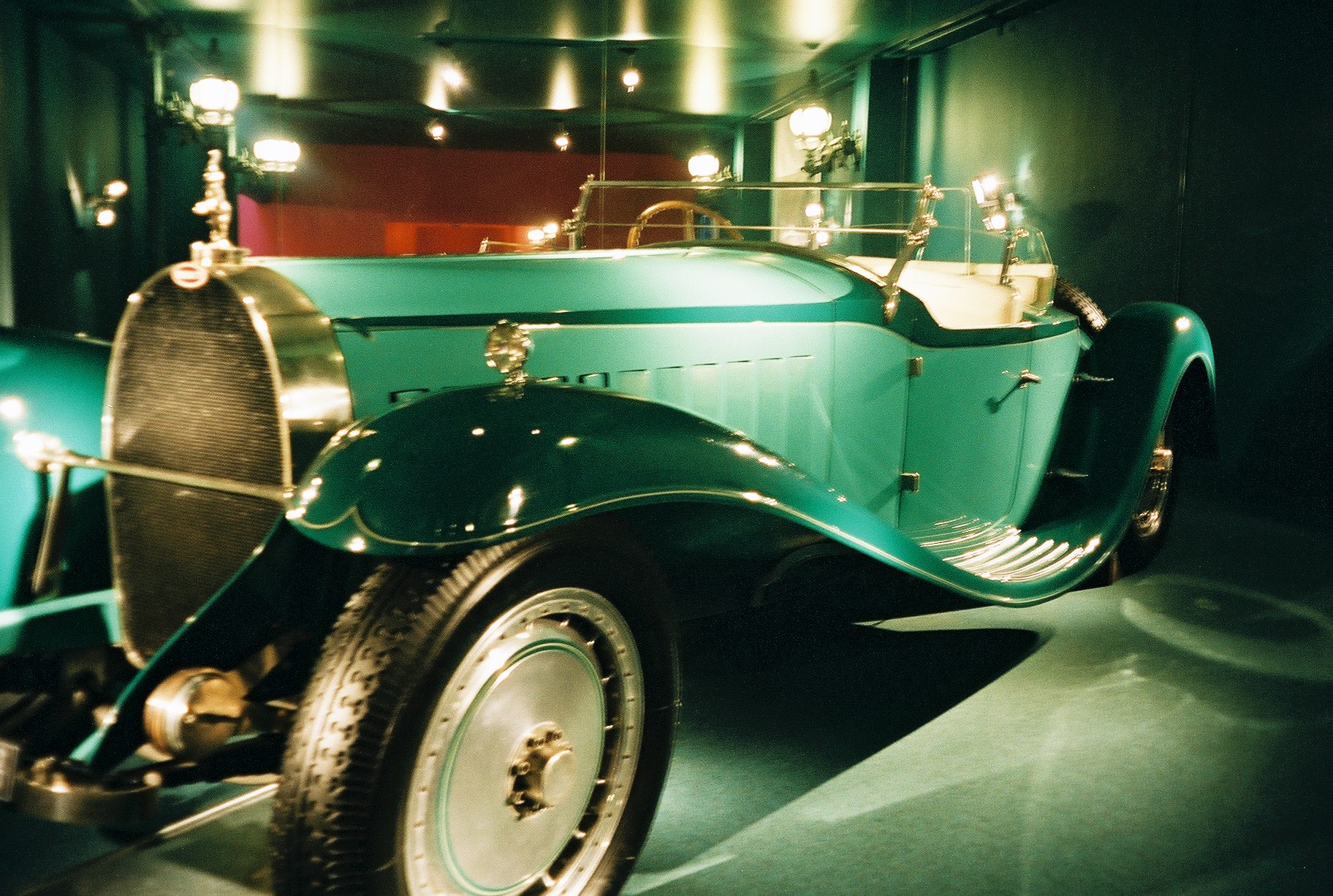

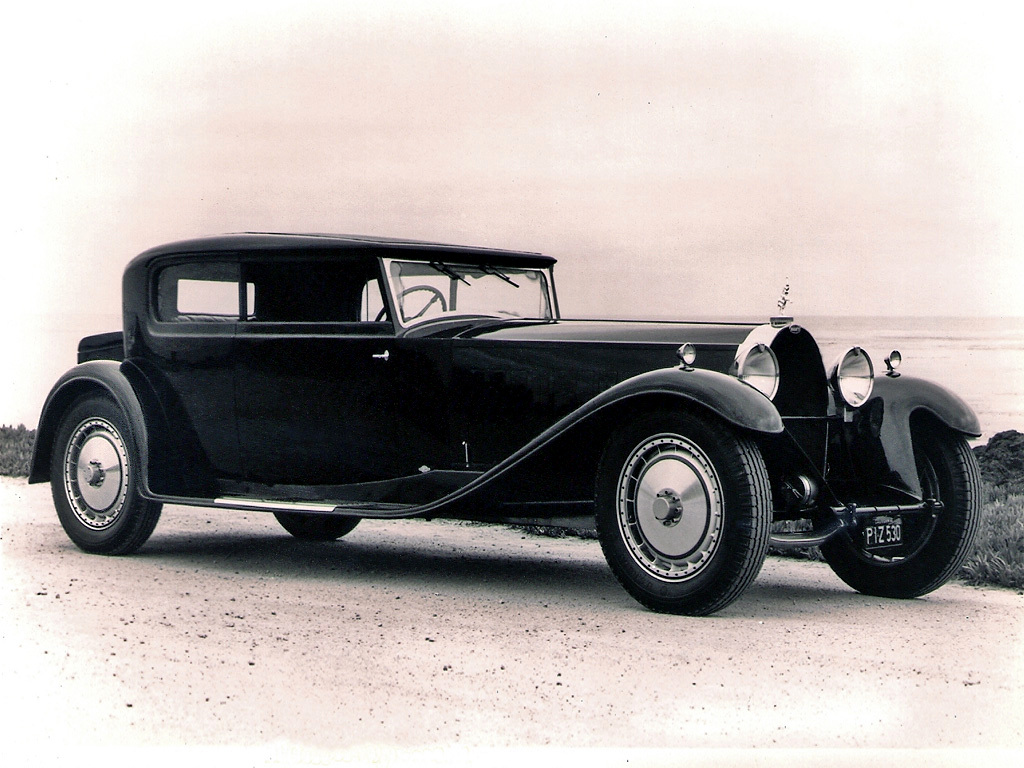

The halo cars of the brand are the Type-41 Royales. Intended to serve the royal families of Europe, they were the largest and most elagent cars of the era. Tony Hogg, in a R&T Salon article, referred to the Kellner Coupe’ as the world’s largest race car; so impressed was he with the car’s mechanical elements. Of the six Type-41’s originally built, seven survive:

41-100 The Napoleon

41-111 Coupe de Ville

41-131 ParkWard Limousine

41-121 Weinberger Cabriolet “Victoria”

41-150 “Berline de Voyage”

With custom body by Bugatti, the extravagant Type 41 Bugatti was conceived by Ettore Bugatti as the ultimate conveyance of royalty. Ironically, of the six cars built, none were ever sold to royalty. The Type 41 had a wheelbase of 170 inches, the longest of any production car in history, and an eight cylinder 300 horsepower engine. This Royale carried a price tag of $42,000 when new.

41-151 Kellner Coupe’

41-111 bis Esders Roadster Musee’ Re-creation of Jean Bugatti Design

With only three Royales sold from the intended initial run of 25, Bugatti saved the company by applying T-41 engineering and drivelines into rail production.

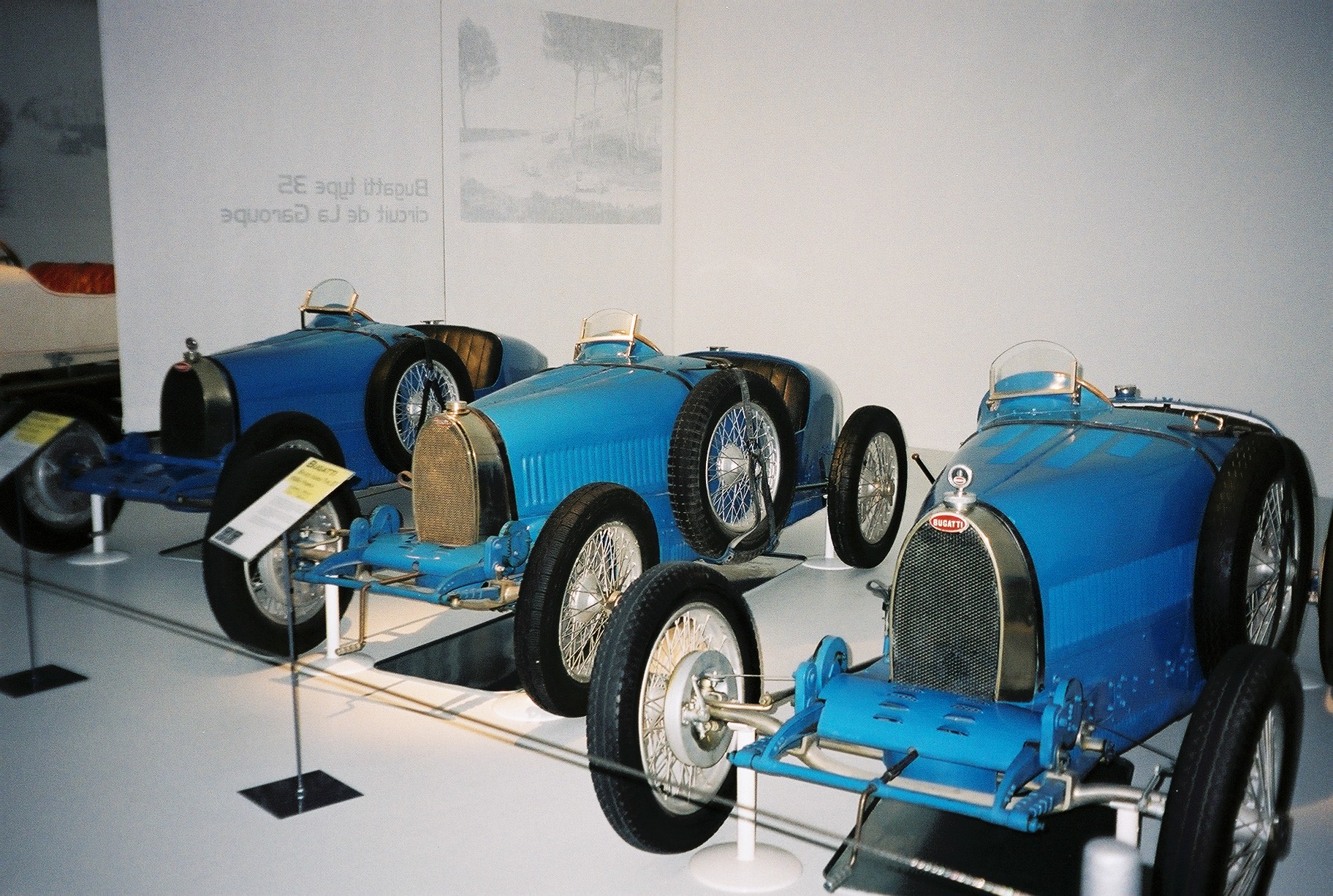

Type-57

Thirty years of Bugatti’s automotive art evolved into the Type 57. The chassis was the most advanced road going design of the era. Malcom Campbell, in 1937, declared it the finest and fastest car available in Europe. Type 57 cars were both coach-built and factory bodied. The Type 57S has a shortened and sporty chassis. The T-57C is a supercharged car, making the T-57SC a supercharged car on a short wheelbase.

Chassis: 57819

Featured is one of the very last Type 57 Cs produced; number 90 of 96. Despite the grim political situation of the day, the rolling chassis was sold to the German Bugatti importer (the last Bugatti to be delivered new to Germany). He in turn shipped the Bugatti chassis to Berlin to be fitted with this highly unusual cabriolet body by coachbuilder Voll & Ruhrbeck. The most striking feature of the German design is the ‘waterfall’ style grille, which was the result of wind tunnel testing and was supposed to improve the car’s aerodynamics.

Carefully hidden away, the unique Bugatti survived the War virtually undamaged. After the war, claiming the car was stolen from a Polish citizen, the country’s minister of transport Tadeusz Tabincki confiscated the car. Once in Poland, it joined Tadeusz’ vast collection of historic cars, which was later reported to consist of 100 vehicles. In the late 1960s he descretely started to sell his cars to the West and so 57819 emerged again. One of the subsequent owners had the body removed and replaced by a Atlantic replica body. Fortunately theVoll & Ruhrbeck body was safely stored.

Almost forty years later, the current owner tracked down both the chassis and unique body and purchased both. Stressing that the body had to remain as original as possible, he shipped the chassis and coachwork to RM Restorations for a ground-up restorations. To the joy of all involved very little work had to be done to the body and it fitted right back on the chassis as if it had never been removed. Four years later the work was completed and the unique Bugatti made a very strong ‘debut’ at the 2006 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, where it secured a ‘Best in Class’ and was one of three runner’s up to the ‘Best of Show’.

Jean Bugatti’s 1000hp Land Speed Car

We can only imagine how thrilling it would have been!

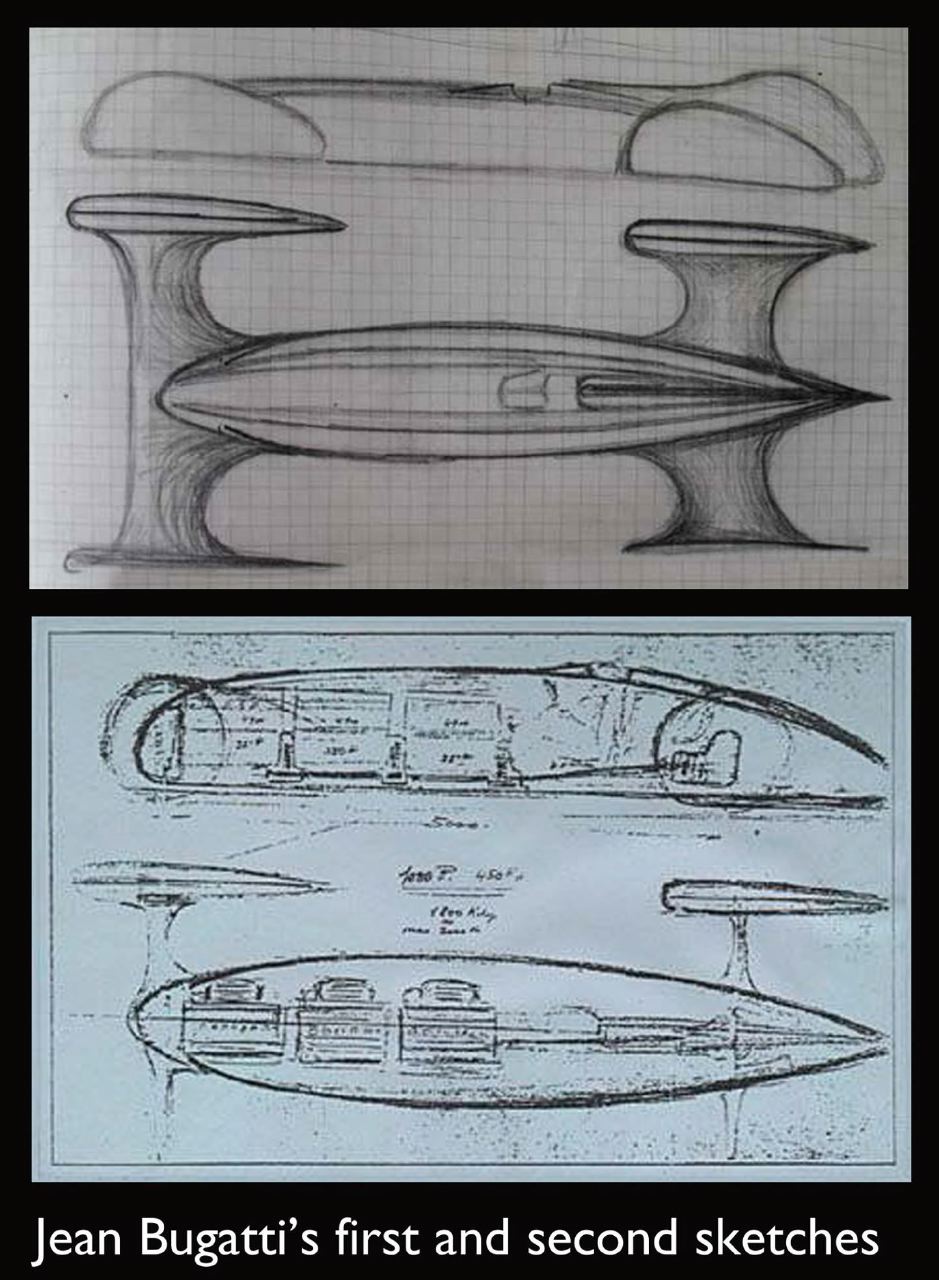

Researching Bugatti images on the internet reveals a very poor quality but intriguing image of a drawing that was attributed to Jean Bugatti.

Researching Bugatti images on the internet reveals a very poor quality but intriguing image of a drawing that was attributed to Jean Bugatti.

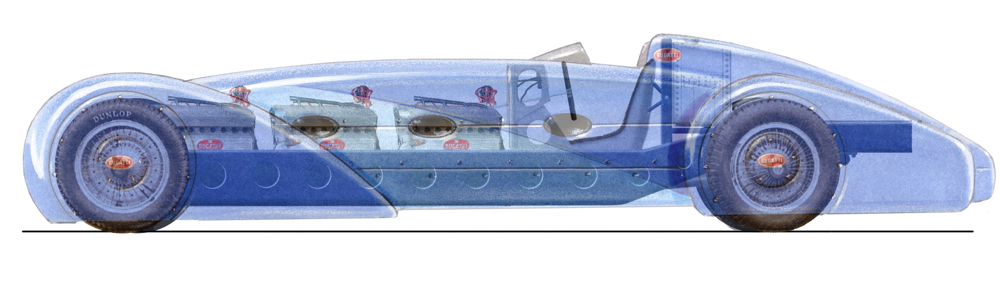

The drawing showed side view and plan sketches of a Land Speed Record car that appeared to have three engines within a dramatically streamlined body. The 1930s “back of envelope” plan and side views (top) fit together perfectly.

This proposed French competitor to the Auto Union was to be driven to a record speed of 400 km/h (248mph) by Bernd Rosemeyer on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn in October 1937. Imagine how this remarkable project might have looked.

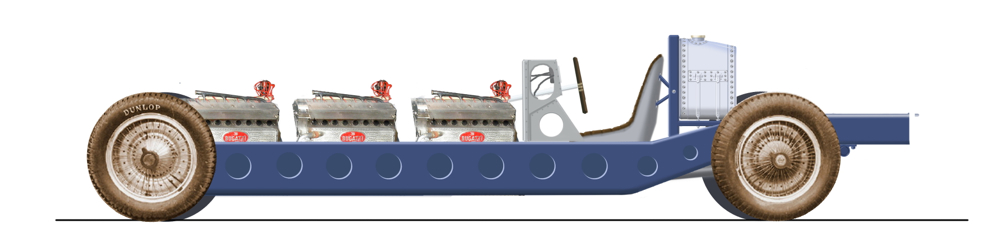

The Bugatti Trust has some basic information about the proposed record-breaker. The single-seater was to have used three 4.9-litre supercharged Type 50B engines, and power was expected to be about 1000bhp. The drive was taken by a short prop-shaft through a double step-up gearset to a rear-mounted gearbox integral with the rear axle casing.

The chassis would have been enormous: the wheelbase was no less than 5.0m (more than 16ft) with a track width of 2.3m (seven and a half feet). Weight was estimated at between 1800 and 2000 kg.

The Jean Bugatti sketch appears to date from early 1937 and it is thought that it was part of a submission to the French government for funding for three record-breaking projects: the rail world speed record (ultimately raised to 196km/h by the Bugatti Royale-engined railcar); the P100 record attempt aircraft; and the one-kilometre and one-mile public road automobile records. With WWII approaching, funding for the aircraft project was forthcoming. However, the French government was not convinced by the “cultural” benefits of the car, causing Jean Bugatti to abandon the idea.

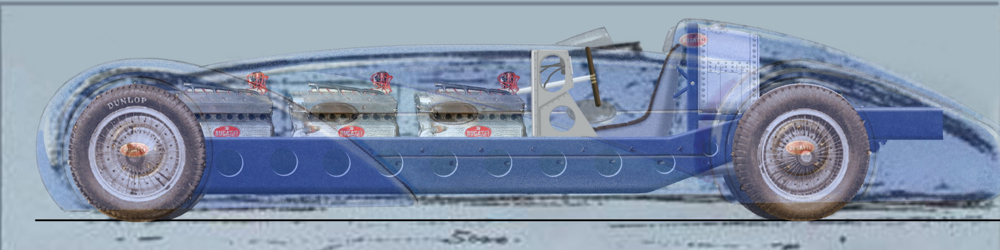

Using the poor quality sketch as a basis for a set of illustrations, a side view of a type 50B engine, when reduced to the same scale, fits perfectly into the chassis, as does a set of Type 59 wheels and tyres. The wheels fitted within the elegant wheel fairings, allowing for a steering lock of around 18 degrees.

Using the poor quality sketch as a basis for a set of illustrations, a side view of a type 50B engine, when reduced to the same scale, fits perfectly into the chassis, as does a set of Type 59 wheels and tyres. The wheels fitted within the elegant wheel fairings, allowing for a steering lock of around 18 degrees.

This all suggests that although the original Jean Bugatti sketch was little more than a “back of an envelope” doodle, he had an excellent grasp of the size and proportion of the mechanical elements of Bugatti cars.

There are some suggestions that Jean was considering monocoque construction for the chassis but this would have been contrary to all accepted practice at Molsheim and would have created difficulties in mounting the three engines. The chassis structure of the successful Type 59 Grand Prix cars would have been a much better understood technology in 1938.

By overlaying various elements of the original sketch, a side view concept of how the chassis and engines could have appeared, and an illustration of the aerodynamically sophisticated body, it is possible to build up an idea of how this spectacular machine might have looked in the late 1930s.

Sadly money was not made available to Ettore Bugatti and his highly creative son Jean and we therefore can only imagine how thrilling this 450km/h Bugatti would have been.

Musee National de L’Automobile

Schumpf Collection

Mulhouse, France